‘I Serve As a Stepping Stone’

The Citadel Fought the Admission of Women. Now a Female Cadet Leads the Corps.

Photographed and written for the New York Times

For most of its 176-year history, the Citadel, a military college in South Carolina, did not admit undergraduate women. That changed in 1995, with a Supreme Court ruling.

But it wasn’t until last year that the school appointed its first woman regimental commander — in essence the head of the student body who leads the corps’ five battalions and 21 companies.

That honor went to 22-year-old Sarah Zorn, now a second lieutenant in the Army.

I began documenting Ms. Zorn, a business administration major for Florida, when she took command in May. I watched as she welcomed the incoming freshman class, met weekly with administrators and led her fellow students in physical training exercises.

Her role was not unlike her job as the leader of her peers: If a cadet stumbled, Ms. Zorn would lift them up. If another struggled, she would encourage them.

The job of top cadet is to tell subordinates — some 2,400 cadets — what to do.

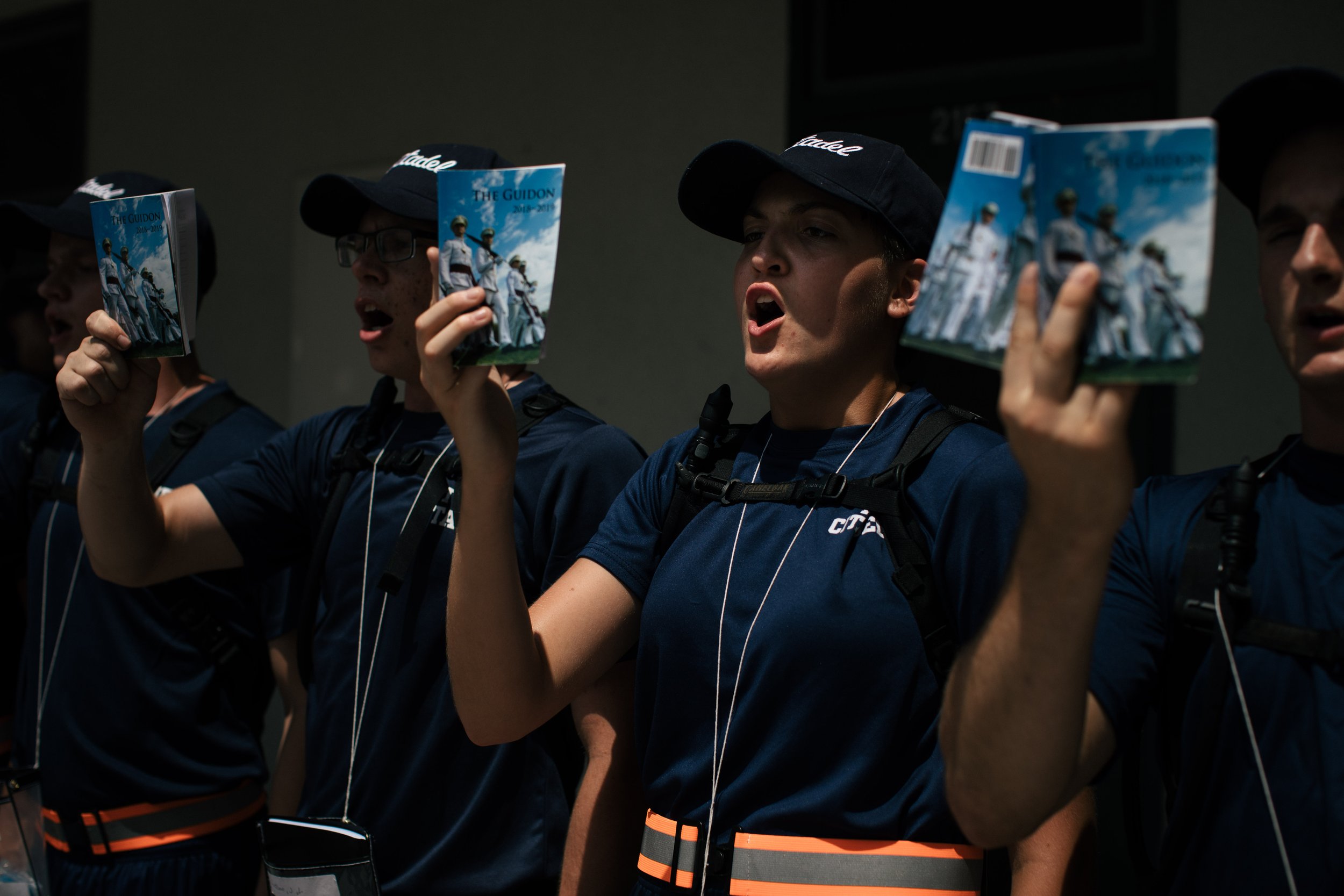

That included 837 freshman recruits, called “knobs” because their shaved heads make them look like doorknobs.

“You’re treated as an equal,” Ms. Zorn said of her classmates and school leaders. “And you are expected to perform as an equal.”

The South Carolina State Legislature founded the Citadel in 1842.

The college did not enroll a Black student until 1966 — more than a decade after public schools were desegregated in Brown v. Board of Education. It took three more decades before the Citadel allowed women to attend its undergraduate program.

In 1995, after a two-year fight in court, Shannon Faulkner won the right to enroll as the first female cadet at the Citadel. She dropped out after the first week, citing exhaustion and emotional abuse. On campus, the cadets celebrated her departure.

Twenty-four years later, women now make up 10 percent of the Citadel student body and 25 percent of students are of color, according to the institution.

“I’d love to see the population of women here go from 10 percent to 50 percent,” Ms. Zorn said.

Over the past year, the school saw a record number of female applicants — something the Citadel’s president, Gen. Glenn Walters, a retired marine, attributed to Ms. Zorn.

“I serve as a stepping stone for everything else that is going to come for the Citadel,” Ms. Zorn said.

When Ms. Zorn applied for admission at the Citadel, she knew little about the legal battle that had forced the college to accept women.

Her mother died when she was 16. Ms. Zorn moved in with her aunt in South Carolina, where she joined her high school’s Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps program and eventually earned an Army scholarship.

Her aunt’s family became like her own.

Six months before Ms. Zorn started college classes, her aunt learned she had an aggressive form of liver cancer. She died two days after Ms. Zorn moved to campus.

Ms. Zorn applied to become top cadet in her junior year. She said it was part of her mission to help repair the reputation of the historic institution.

“We want to make sure that people are aware of what happened here at the Citadel,” Ms. Zorn said. “So that we can understand and make sure we don’t repeat it.”

In March, she helped organize an event for students to talk openly about sexual assault. The rate of sexual assault in the United States military increased by 38 percent from 2016 to 2018, according to a recent Pentagon report.

She helped shape the policy overturning a rule requiring first-year women to cut their hair to three inches or shorter.

“Subconsciously, somewhere in the deepest darkest laters of Citadel history, that was an underlying symbol of oppression of women on the Citadel campus,” she said.

She also pushed openly for the inclusion of women and people of color in leadership roles, often passing on opportunities to address the student body to her second in command, David Days.

When asked how she felt that the role would return to a white man, she said: “I have complete faith, trust and confidence that he was picked because he is the right person for the job.”

This month, Ms. Zorn’s tenure came to an end. She graduated on May 4, passing the regimental commander’s sword to her successor, Richard Snyder.

Ms. Zorn will serve the next eight years in the Army as a field artillery officer.

As her graduation ceremony, she joined nearly 500 seniors walking in alphabetical order across a brightly lit stage to collect their diplomas.

In Citadel tradition, the last cadet to cross the stage — the graduate whose name falls last in the alphabet — gets to speak. Ms. Zorn stood at the podium and addressed her fellow graduates, smiling.

“We survived — female regimental commander and all,” she said.